Every cognitive bias exists for a reason—primarily to save our brains time or energy.

I’ve spent many years referencing Wikipedia’s list of cognitive biases whenever I have a hunch that a certain type of thinking is an official bias but I can’t recall the name or details. But despite trying to absorb the information of this page many times over the years, very little of it seems to stick.

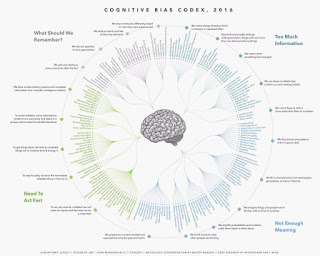

I decided to try to more deeply absorb and understand this list by coming up with a simpler, clearer organizing structure. If you look at these biases according to the problem they’re trying to solve, it becomes a lot easier to understand why they exist, how they’re useful, and the trade-offs (and resulting mental errors) that they introduce.

Four problems that biases help us address: Information overload, lack of meaning, the need to act fast, and how to know what needs to be remembered for later.

Problem 1: Too much information

There is just too much information in the world; we have no choice but to filter almost all of it out. Our brain uses a few simple tricks to pick out the bits of information that are most likely going to be useful in some way.

- We notice things that are already primed in memory or repeated often. This is the simple rule that our brains are more likely to notice things that are related to stuff that’s recently been loaded in memory.

- See: Availability heuristic, Attentional bias, Illusory truth effect, Mere exposure effect, Context effect, Cue-dependent forgetting, Mood-congruent memory bias, Frequency illusion, Baader-Meinhof Phenomenon, Empathy gap, Omission bias, or the Base rate fallacy.

- Bizarre/funny/visually-striking/anthropomorphic things stick out more than non-bizarre/unfunny things. Our brains tend to boost the importance of things that are unusual or surprising. Alternatively, we tend to skip over information that we think is ordinary or expected.

- See: Bizarreness effect, Humor effect, Von Restorff effect, Picture superiority effect, Self-relevance effect, or Negativity bias.

- We notice when something has changed—and we’ll generally tend to weigh the significance of the new value by the direction the change happened (positive or negative) more than re-evaluating the new value as if it had been presented alone. This also applies to when we compare two similar things.

- See: Anchoring, Contrast effect, Focusing effect, Money illusion, Framing effect, Weber–Fechner law, Conservatism, or Distinction bias.

- We are drawn to details that confirm our own existing beliefs. This is a big one. As is the corollary: we tend to ignore details that contradicts our own beliefs.

- See: Confirmation bias, Congruence bias, Post-purchase rationalization, Choice-supportive bias, Selective perception, Observer-expectancy effect, Experimenter’s bias, Observer effect, Expectation bias, Ostrich effect, Subjective validation, Continued influence effect, or Semmelweis reflex.

- We notice flaws in others more easily than flaws in ourselves. Yes, before you see this entire article as a list of quirks that compromise how other people think, realize that you are also subject to these biases.

- See: Bias blind spot, Naïve cynicism, or Naïve realism.

Problem 2: Not enough meaning

The world is very confusing, and we end up only seeing a tiny sliver of it—but we need to make some sense of it in order to survive. Once the reduced stream of information comes in, we connect the dots, fill in the gaps with stuff we already think we know, and update our mental models of the world.

- We find stories and patterns even in sparse data. Since we only get a tiny sliver of the world’s information, and also filter out almost everything else, we never have the luxury of having the full story. This is how our brain reconstructs the world to feel complete inside our heads.

- See: Confabulation, Clustering illusion, Insensitivity to sample size, Neglect of probability, Anecdotal fallacy, Illusion of validity, Masked man fallacy, Recency illusion, Gambler’s fallacy, Hot-hand fallacy, Illusory correlation, Pareidolia, or Anthropomorphism.

- We fill in characteristics from stereotypes, generalities, and prior histories whenever there are new specific instances or gaps in information. When we have partial information about a specific thing that belongs to a group of things we are pretty familiar with, our brain has no problem filling in the gaps with best guesses or what other trusted sources provide. Conveniently, we then forget which parts were real and which were filled in.

- See: Group attribution error, Ultimate attribution error, Stereotyping, Essentialism, Functional fixedness, Moral credential effect, Just-world hypothesis, Argument from fallacy, Authority bias, Automation bias, Bandwagon effect, or the Placebo effect.

- We imagine things and people we’re familiar with or fond of as better than things and people we aren’t familiar with or fond of. Similar to the above, but the filled-in bits generally also include built-in assumptions about the quality and value of the thing we’re looking at.

- See: Halo effect, In-group bias, Out-group homogeneity bias, Cross-race effect, Cheerleader effect, Well-traveled road effect, Not invented here, Reactive devaluation, or the Positivity effect.

- We simplify probabilities and numbers to make them easier to think about. Our subconscious mind is terrible at math and generally gets all kinds of things wrong about the likelihood of something happening if any data is missing.

- See: Mental accounting, Normalcy bias, Appeal to probability fallacy,Murphy’s Law, Subadditivity effect, Survivorship bias, Zero sum bias, Denomination effect, or Magic number 7+-2.

- We think we know what others are thinking. In some cases this means that we assume that they know what we know, in other cases we assume they’re thinking about us as much as we are thinking about ourselves. It’s basically just a case of us modeling their own mind after our own (or in some cases, after a much less complicated mind than our own).

- See: Curse of knowledge, Illusion of transparency, Spotlight effect, Illusion of external agency, Illusion of asymmetric insight, or the Extrinsic incentive error.

- We project our current mindset and assumptions onto the past and future. Magnified also by the fact that we’re not very good at imagining how quickly or slowly things will happen or change over time.

- See: Hindsight bias, Outcome bias, Moral luck, Declinism, Telescoping effect, Rosy retrospection, Impact bias, Pessimism bias, Planning fallacy, Time-saving bias, Pro-innovation bias, Projection bias, Restraint bias, or the Self-consistency bias.

Problem 3: The need to act fast

We’re constrained by time and information, and yet we can’t let that paralyze us. Without the ability to act fast in the face of uncertainty, we surely would have perished as a species long ago. With every piece of new information, we need to do our best to assess our ability to affect the situation, apply it to decisions, simulate the future to predict what might happen next, and otherwise act on our new insight.

- In order to act, we need to be confident in our ability to make an impact and to feel like what we do is important. In reality, most of this confidence can be classified as overconfidence, but without it we might not act at all.

- See: Overconfidence effect, Egocentric bias, Optimism bias, Social desirability bias, Third-person effect, Forer effect, Barnum effect, Illusion of control, False consensus effect, Dunning-Kruger effect, Hard-easy effect, Illusory superiority, Lake Wobegone effect, Self-serving bias, Actor-observer bias, Fundamental attribution error, Defensive attribution hypothesis, Trait ascription bias, Effort justification, Risk compensation, or the Peltzman effect.

- In order to stay focused, we favor the immediate, relatable thing in front of us over the delayed and distant. We value stuff more in the present than in the future, and relate more to stories of specific individuals than anonymous individuals or groups. I’m surprised there aren’t more biases found under this one, considering how much it impacts how we think about the world.

- See: Hyperbolic discounting, Appeal to novelty, or the Identifiable victim effect.

- In order to get anything done, we’re motivated to complete things that we’ve already invested time and energy in. The behavioral economist’s version of Newton’s first law of motion: an object in motion stays in motion. This helps us finish things, even if we come across more and more reasons to give up.

- See: Sunk cost fallacy, Irrational escalation, Escalation of commitment, Loss aversion, IKEA effect, Processing difficulty effect, Generation effect, Zero-risk bias, Disposition effect, Unit bias, Pseudocertainty effect, Endowment effect, or the Backfire effect.

- In order to avoid mistakes, we’re motivated to preserve our autonomy and status in a group, and to avoid irreversible decisions.If we must choose, we tend to choose the option that is perceived as the least risky or that preserves the status quo. Better the devil you know than the devil you do not.

- See: System justification, Reactance, Reverse psychology, Decoy effect, Social comparison bias, or Status quo bias.

- We favor options that appear simple or that have more complete information over more complex, ambiguous options. We’d rather do the quick, simple thing than the important complicated thing, even if the important complicated thing is ultimately a better use of time and energy.

- See: Ambiguity bias, Information bias, Belief bias, Rhyme as reason effect, Bike-shedding effect, Law of Triviality, Delmore effect, Conjunction fallacy, Occam’s razor, or the Less-is-better effect.

Problem 4: What should we remember?

There’s too much information in the universe. We can only afford to keep around the bits that are most likely to prove useful in the future. We need to make constant bets and trade-offs around what we try to remember and what we forget. For example, we prefer generalizations over specifics because they take up less space. When there are lots of irreducible details, we pick out a few standout items to save, and discard the rest. What we save here is what is most likely to inform our filters related to information overload (problem #1), as well as inform what comes to mind during the processes mentioned in problem #2 around filling in incomplete information. It’s all self-reinforcing.

- We edit and reinforce some memories after the fact. During that process, memories can become stronger, however various details can also get accidentally swapped. We sometimes accidentally inject a detail into the memory that wasn’t there before.

- See: Misattribution of memory, Source confusion, Cryptomnesia, False memory, Suggestibility, or the Spacing effect.

- We discard specifics to form generalities. We do this out of necessity, but the impact of implicit associations, stereotypes, and prejudice results in some of the most glaringly bad consequences from our full set of cognitive biases.

- See: Implicit associations, Implicit stereotypes, Stereotypical bias, Prejudice, Negativity bias, or the Fading affect bias.

- We reduce events and lists to their key elements. It’s difficult to reduce events and lists to generalities, so instead we pick out a few items to represent the whole.

- See: Peak–end rule, Leveling and sharpening, Misinformation effect, Duration neglect, Serial recall effect, List-length effect, Modality effect, Memory inhibition, Part-list cueing effect, Primacy effect, Recency effect, Serial position effect, or the Suffix effect.

- We store memories differently based on how they were experienced. Our brains will only encode information that it deems important at the time, but this decision can be affected by other circumstances (what else is happening, how is the information presenting itself, can we easily find the information again if we need to, etc.) that have little to do with the information’s value.

- See: Levels of processing effect, Testing effect, Absent-mindedness, Next-in-line effect, Tip of the tongue phenomenon, or the Google effect.

Great, how am I supposed to remember all of this?

You don’t have to. But you can start by remembering these four giant problems our brains have evolved to deal with over the last few million years (and maybe bookmark this page if you want to occasionally reference it for the exact bias you’re looking for):

- Information overload sucks, so we aggressively filter.

- Lack of meaning is confusing, so we fill in the gaps.

- We need to act fast lest we lose our chance, so we jump to conclusions.

- This isn’t getting easier, so we try to remember the important bits.

In order to avoid drowning in information overload, our brains need to skim and filter insane amounts of information and quickly, almost effortlessly, decide which few things in that firehose are actually important, and call those out.

In order to construct meaning out of the bits and pieces of information that come to our attention, we need to fill in the gaps, and map it all to our existing mental models. In the meantime, we also need to make sure that it all stays relatively stable and as accurate as possible.

In order to act fast, our brains need to make split-second decisions that could impact our chances for survival, security, or success, and we need to feel confident that we can make things happen.

And in order to keep doing all of this as efficiently as possible, our brains need to remember the most important and useful bits of new information and inform the other systems so they can adapt and improve over time, but make sure to remember no more than that.

Sounds pretty useful! So what’s the downside?

In addition to the four problems, it would be useful to remember these four truths about how our solutions to these problems have problems of their own:

- We don’t see everything. Some of the information we filter out is actually useful and important.

- Our search for meaning can conjure illusions. We sometimes imagine details that were filled in by our assumptions, and construct meaning and stories that aren’t really there.

- Quick decisions can be seriously flawed. Some of the quick reactions and decisions we jump to are unfair, self-serving, and counter-productive.

- Our memory reinforces errors. Some of the stuff we remember for later just makes all of the above systems more biased, and more damaging to our thought processes.

By keeping these four problems and their four consequences in mind, the availability heuristic (and, specifically, the Baader-Meinhof phenomenon) will ensure that we notice our own biases more often. If you visit this page to refresh your memory every once in a while, the spacing effect will help underline some of these thought patterns so that your bias blind spot and naïve realism is kept in check.

Nothing we do can make the four problems go away (until we have a way to expand our minds’ computational power and memory storage to match that of the universe), but if we accept that we are permanently biased—and that there’s room for improvement—confirmation bias will continue to help us find evidence that supports this, which will ultimately lead us to better understand ourselves.

No comments:

Post a Comment